This last weekend’s live fire adventure was very much a team effort. Polly had a great idea for a dish, I did the meat cooking and she did the marinading and the veg which is often how we roll, but perhaps her contribution is not always conveyed in full by my use of language. Perhaps I just want to hog all the credit. My blog, my rules.

The dish in question was inspired by the appearance of Scottish comedian Fern Brady on the Off Menu podcast hosted by James Acaster and Ed Gamble. If you haven’t come across the show, it is definitely worth a listen. In this episode, Fern introduced us to the concept of “shite calories”; those where you eat something and are immediately filled with hard, bitter regret. Things like extra cheap, sugary biscuits that really taste of nothing, those soft, bland pastries which count as “breakfast” at a conference, or a glass of acid reflux wine are all classed as shite calories. It is a pithy mantra to keep in mind when hungry and the temptation is that “anything will do”, so we have adopted it into our everyday lexicon to remind ourselves to try to eat a little better. There is nothing more satisfying than eating something that you have made yourself, and this has the benefit that you know what went into it and the calories are all accounted for. However, the point of this blog is not to hector the reader about what they should or should not be eating, it is to explore the joy to be had in cooking with fire! And thus, we move to Jianbing, the Chinese crepes described so eloquently by Fern on the podcast. She gets hers from the Chinese Tapas House which is on Little Newport Street at the Charing Cross Road end of Chinatown nearest to Leicester Square tube. Polly was in town to watch a play and got one. After 2 bites she rang me and said, through a mouthful of crepe, that this really was a taste sensation, and I should definitely get one the next time. I did. I had no regrets.

Jianbing are made using those big, flat, circular griddles you see in every French market, but here the batter is a little more glutinous. A ladle full is poured into the middle of the griddle and spread around to form a perfect circle. Once one side is cooked, the Jianbing is flipped and an egg is cracked onto the cooked side and stirred around a bit. The whole thing is flipped back again to cook the egg, and the filling ingredients are then laid on the top, after Tianmian, a sweet, spicy, mahogany-hued sauce is brushed over – you can ask for it to be extra hot and I encourage you to do so. The one I had contained pork belly. coriander, spring onion, deep-fried wonton wrappers to add a lovely crunchy texture and a random frankfurter which I was not altogether convinced was a traditional ingredient. Once ready, the whole thing is wrapped up, not unlike a burrito and handed over. These things come off the griddle so hot that you have to hold them with alternating fingers, like those lizards cooling their feet in the Namib desert, and so you have plenty of time to walk to Leicester Square itself to sit on one of the benches and watch the tourists whilst you wait for your Jianbing to cool to eating temperature. Fern is not wrong; they are delicious and really filling with not a single dodgy calorie anywhere. A perfect breakfast/brunch/lunch option.

Fast forward to last weekend and we saw a 1.5kg boneless pork shoulder in Aldi and thought we’d give making Jianbing a lash, using the pork as the main filling. Polly had seen a good recipe for Char Siu pork on the BBC food website – CLICK HERE if you want to give it a go yourself. If the Arctic winds are cutting through to your very marrow too much to light a fire outside to cook at this time of year, the recipe handily explains how to do it in the oven.

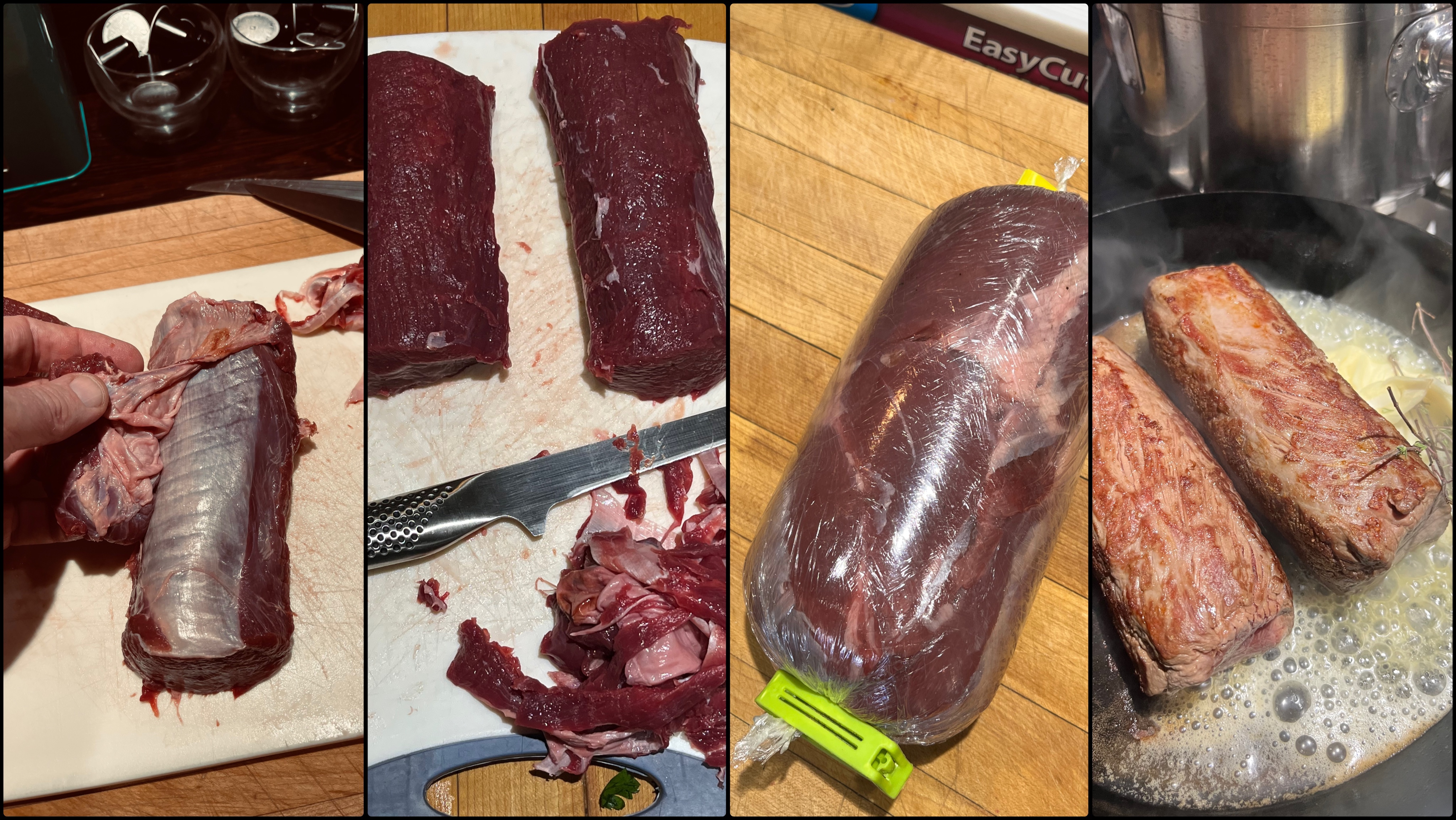

On Saturday, we cut the shoulder into 4 reasonably even chunks and marinaded overnight in hoi sin sauce, garlic, ginger, soy, rice vinegar and swapped the sugar in the recipe for a bit of our friend Guy’s honey. Sunday was bright, clear and freezing – a perfect day to get the Big Green Egg going; once lit, I set the vents to get it to about 150°c and added the plate setter for indirect cooking. The pork went straight on the wire rack, with a bit of foil underneath to catch the drips. I used hickory smoking wood, but pretty much anything that has a bit of punch to it like oak or cherry would work I reckon. The recipe said to cook for about 90 minutes, but I wanted a bit more of the fat to render out, so I let it go a bit longer. The internal temperature got to 75°c which seemed about right; definitely cooked enough to eat, but not so much it turned into pulled pork (I bet it would be great if you let it get that far though). The initial test slices where very much better than satisfactory. There was a lovely pink smoke ring around the periphery and just enough smoke flavour for it not to be totally obscured by the deep flavours of the marinade. That said, I think next time we would beef up the level of chilli and maybe add some 5 spice in the marinade. The finished pork was really delicious, but probably would be even better with a slightly denser Oriental flavour and a bit more heat. Maybe a bit of a sear over direct heat at the end would be good too

Meanwhile, Polly had made the batter for the crepes which is basically a 50:50 mixture of plain flour, wholemeal flour and about the equivalent weight of water – you end up with a sort of double cream consistency. She had also finely chopped fresh chillies, coriander, spring onions and chives and in true TV chef style arranged all these neatly into little bowls (you should do this too – not only does it make you feel like Michel Roux Jr, it also makes everything a bit easier once you get to the business end of the cooking). While the pork was resting, I reduced the remaining marinade down on the hob to use as the sauce to brush onto the crepe. It got a good bit thicker and syrupier – I think this was an additional benefit of using the honey instead of the sugar.

Now to the cooking of the crepes. If you’ve ever made pancakes, you will know the first one always turns out really badly and this was no exception. This was largely down to two reasons. The first is that having seen the film Dark Waters a year or two ago, we got freaked out by the historical horrors of DuPont dumping Teflon chemicals in the water supply and so, since then, our cheap, slightly peeling non-stick pans have been relegated to camping use only. The lovely Le Creuset frying pan we have is a vintage charity shop special. It weighs about the same as a very fat cat, so takes ages to heat up and thus we arrived at reason 2; it just wasn’t hot enough. Our first attempt went in the bin. I am all for reducing food waste so please heed my warnings if you have a crack at this yourself. All the fashionable young Instagram chefs are using Hexclad pans these days which are apparently excellently non-stick, but these do come with a hefty price tag, so we persisted with our cast iron, enamelled (not quite) non-stick pan. I think next time I would use the big, flat, square steel plancha I got from Axel Perkins which would have the advantage that there is no lip and so it would be easier to get the crepe a bit thinner and to slide a flat palette knife underneath to loosen and flip it. If you are having a go at this recipe, definitely leave it for longer than you think necessary on the first side; a lot of water needs to evaporate before it can be turned over.

Once we switched the pan onto the biggest ring, with the fiercest flame and a bit more oil, we made our second crepe more successfully than the first, cracked the egg over it, flipped it back, brushed over the reduced marinade, filled it with the chopped veg and a crushed handful of Thai crackers in lieu of the wonton wrappers. On top of that went a couple of thick slices of the Char Siu pork and then we folded it. Honestly, it was so good. Not as good as the Chinese Tapas House, but pretty bloody fantastic. We made another one for the sake of practice, then a third just to be sure. Since this was all home-made, we were fairly comfortable that the calories we had consumed were anything but shite and, if you have spent time on the marinading and the smoking and everything else, I am sure you will feel the same glow of satisfaction that we did. Also, 1.5kg of pork shoulder goes a long way, so we have leftovers to craft into something in the week. If you wanted a leaner option, you could use pork loin instead of shoulder, but you would need to be very careful when cooking it to not let it dry out. I am sure chicken would work really well and for vegetarians I wonder if you could marinade and cook a few of those enormous Portobello mushrooms to go in your Jianbing. Go on, give these a go and let me know how you get on.